To the extent that historical press releases reference BMW Manufacturing Co., LLC as the manufacturer of certain X model vehicles, the referenced vehicles are manufactured in South Carolina with a combination of U.S. origin and imported parts and components.

PressClub USA · Article.

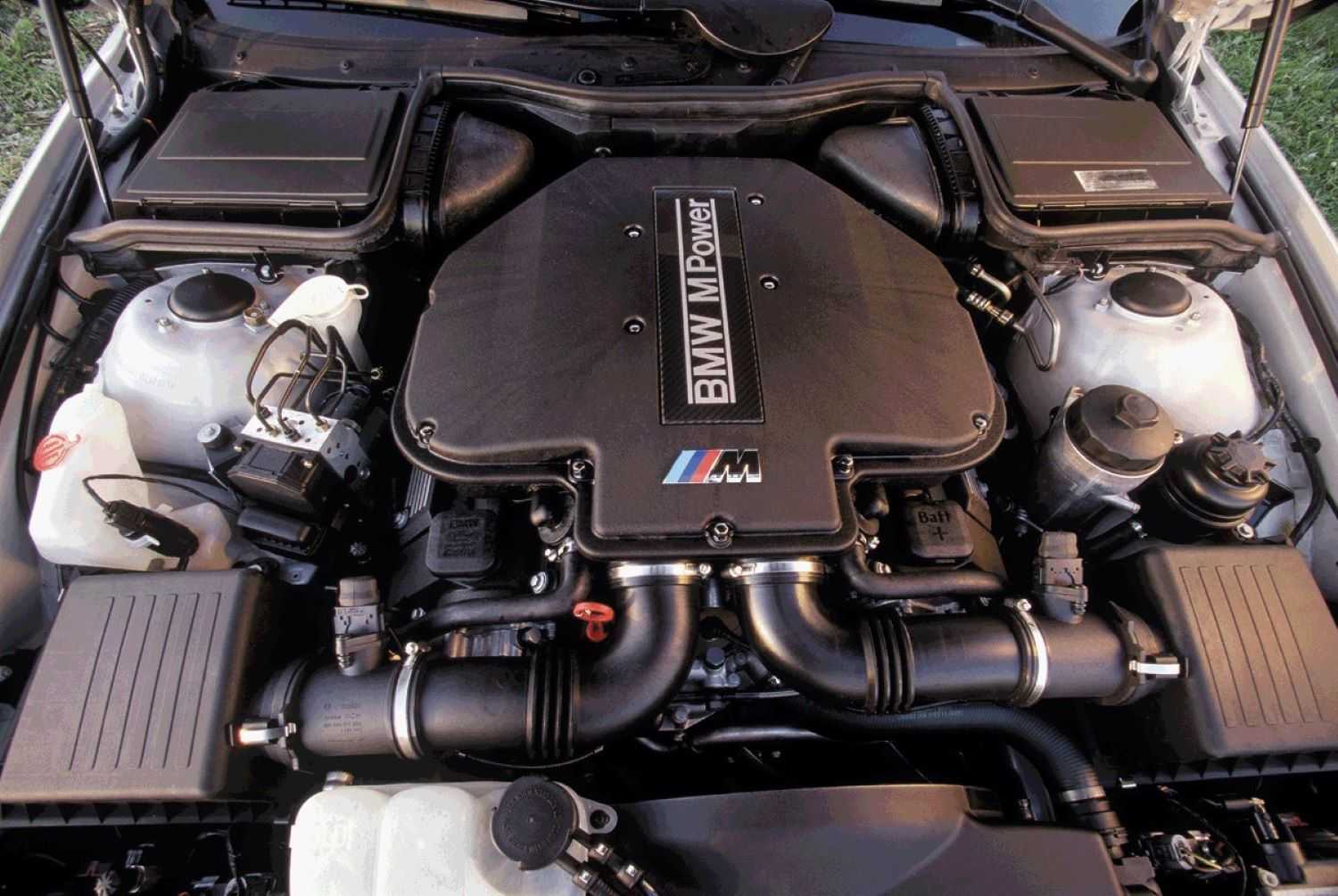

BMW NA 50th Anniversary | 50 Stories for 50 Years Chapter 29: “The Third Generation BMW M5 [E39] V8 Power for the Executive Express

Fri Jul 25 18:16:00 CEST 2025 Press Release

Although invented in France, V8 engines have been indelibly associated with American cars—and American tastes—since 1914, when Cadillac introduced its “L-head” V8. Since then, a V8 engine has been de rigueur for any automaker hoping to sell cars to American customers, lest its automobiles be seen as underpowered, underequipped, or simply unappealing.

Contato de imprensa.

Thomas Plucinsky

BMW Group

Tel: +1-201-307-3701

send an e-mail

Autor.

Thomas Plucinsky

BMW Group

Related Links.

Although invented in France, V8 engines have been indelibly

associated with American cars—and American tastes—since 1914, when

Cadillac introduced its “L-head” V8. Since then, a V8 engine has been

de rigueur for any automaker hoping to sell cars to American

customers, lest its automobiles be seen as underpowered,

underequipped, or simply unappealing.

BMW is no exception. In

1956, BMW introduced its first V8, the Oldsmobile-inspired M502, in

several cars aimed squarely at the US market. When that engine went

out of production in 1965, BMW powered its small cars with inline four

cylinder engines, its larger and more upscale cars with the company’s

signature inline sixes. Unfortunately, the latter engines reached

their limitations just as new V8-powered cars from Lexus were taking

the US by storm, forcing BMW to counter with its first new V8 in

nearly four decades. In 1992, the M60 V8 debuted in Europe with the

530i, 540i, and 740i; two years later, it would arrive in the US

powering all three models.

In Garching, BMW’s M division was

facing a similar conundrum. Throughout the early 1990s, the M5 and M6

were still powered by a variant of the 277-horsepower M88 inline six

that debuted in the 1978 M1. The engine had evolved considerably—in

the second-generation E34 M5, the catalyst-equipped, 3.8-liter S38

delivered 340 horsepower—but it had reached its developmental limit.

Moreover, its performance was nearly matched by the lighter and

smaller S50 (later S52) six that debuted in the 1992 E36 M3.

As

the M division began planning the E34 M5’s successor in 1993, it was

clear that a new engine concept would be required for the E39 M5. “We

had two opportunities: a V8 or a turbocharged six-cylinder,” said Alex

Hildebrandt, the E39 M5 Project Leader and Head of Product Management

for the M division then led by Karlheinz Kalbfell.

It wasn’t easy to choose between the two. “We were at the end of

the energy crisis in Europe, and there was some doubt about whether

this kind of car would find further demand on the market,” Hildebrandt

said. “Kalbfell was eager to play this card of fuel efficiency, which

didn’t mean we wouldn’t have powerful engines but that the efficiency

of the engines should be outstanding in comparison to the power. There

was no way to come to that with a V8, because in the end, eight

cylinders have to be fed. We had a lot of discussions about

turbocharging, but at the time turbocharging mainly added fuel

consumption and power at the upper end of the rev range, rather than

torque in the middle.”

While discussions about the M5’s engine

configuration were getting underway, BMW of North America was debating

whether to continue offering M cars in this market. The US market had

absorbed over 50 percent of E28 M5 production, or 1,227 cars, but BMW

NA had struggled to sell its costly successor, the E34 M5 with its

mechanically complex S38 engine. Ultimately, BMW NA moved just 1,476

E34 M5s, or 13 percent of total production. That scenario—together

with limited sales for the even more complex E30 M3—had seen BMW NA

reject the E36 M3 as too expensive and too high-maintenance for the

US, and to consider abandoning the M cars altogether.

The US

market was important to M’s overall viability, however, and Kalbfell

was eager to find an alternative powertrain that would allow the E36

M3 to be sold in the US at a more affordable price while better

suiting American driving conditions. In August 1993, BMW NA agreed to

an engine that sacrificed the “pure” M engine characteristics—high

revs and top-end horsepower, resulting in high technical complexity—in

favor of an engine with nearly as much torque, significantly lower

manufacturing cost, vastly reduced maintenance requirements, and a

more affordable retail price. The US-spec E36 M3 began arriving in

late 1994, and the response exceeded expectations handily. By the end

of 1995, enthusiasts had snapped up 8,515 examples.

That car’s

success demonstrated the appetite for M cars among American customers,

and it offered a convincing argument for an M5 built along similar

lines. Even so, Kalbfell continued to advocate for a six-cylinder

engine throughout 1994 and 1995, eager to retain this crucial link to

BMW’s heritage.

“Kalbfell believed that the heart and soul of

BMW was the inline six-cylinder, and that’s what he wanted as the

image leader for BMW, not a V8,” said Rich Brekus, then Head of

Product Planning for BMW NA. “I guess he saw the V8 as an American

thing, too large and wasteful, but I don’t think anyone could figure

out how to have better performance with a six than what they had with

the S38.”

They certainly tried, considering not only a

turbocharged inline six but a V6, which would have been a total

outlier within the BMW engine universe. “In the end, the company was

not prepared to spend the money to develop an engine for only 2-3,000

cars a year,” Hildebrandt said. “So this idea was buried, but we’d

lost two years of development, a lot of time.”

Eventually, Kalbfell had to concede that a V8 presented the best

technical solution for the M5, and that such an engine would suit the

car’s character, too. “We wanted to create a sports car for gentlemen,

and the V8 was a natural choice,” Hildebrandt said. “And in the end,

it was the only choice to bring the car to market in a reasonable

time. We were two years behind a regular development process, and if

we had gone even later there would have been no profit in the

project.”

Once the V8 concept was established, Hildebrandt took

it to Dr. Wolfgang Reitzle, then Board Member for R&D and Sales,

for final approval. “The economic figures were quite on the edge, and

we were projecting around 8,000-8,500 units over the rather short

lifetime of the model,” Hildebrandt said. “But Reitzle said to his

sales executives, ‘Okay, guys, this car is good enough to put 10,000

in the books.’ That was really the point where the E39 M5 finally came

to life.”

The compressed timeline already limited the development

time available for the V8 engine that had aroused so much discussion;

moreover, BMW had no racing V8 on which to base the M5’s powerplant.

That forced the M engineers to modify the series-production M62 V8,

which had superseded the M60 in 1996 with more displacement, higher

torque output, and improved fuel economy.

To turn the M62 into

the S62, and to do so quickly, the M division had to set aside one of

its most treasured virtues. “M’s philosophy at the time was

high-revving engines, which we couldn’t achieve with the V8 concept we

had,” Hildebrandt said. “We just said, ‘Okay, for this generation M5

we’ll forget about that, if we find other ways to reach the

400-horsepower level.’”

Under the leadership of engine designer Wolfgang Kreinhöfner, the

V8’s redline increased slightly nonetheless, from 5,700 rpm to

6,600—“a level where we felt safe,” Hildebrandt said—while

displacement increased from 4.4 to 5.0 liters within a redesigned

block with Alusil-plated cylinders. The cylinder heads retained the

production M62’s hydraulic valve tappets, marking the debut of this

maintenance-reducing feature on an M engine, with revised porting for

the flow of gases into the combustion chambers. In true M fashion, the

S62’s intake system was equipped with eight throttle bodies, one per

cylinder, controlled not by a linkage but by an electronic servomotor

that also functioned as a cruise control, top-speed limiter, and idle

speed governor.

Most importantly, the S62 got an upgraded oil

system to eliminate oil starvation under hard cornering. “If you did a

quick right-hand corner [with the M62], all the oil went to the left

cylinder bank,” Hildebrandt said. “The engineers created a

torque-controlled oil pressure system to ensure the oil supply to both

cylinders, and we also experimented a lot with the oil-control rings

on the pistons. We only had half the time to develop the engine, and

then two months before the start of production one of the long-term

test engines blew up. The team had to work really hard to eliminate

the mistake, but in the end we made it. And then we used this engine

for the Z8, as well.”

The S62 V8 was mated to the standard 5

Series’ driveline, including the Getrag 420G six-speed manual

transmission that was rated for engines producing up to 368 pound-feet

of torque: exactly the amount delivered by the S62, along with 400

horsepower. The transmission was followed by a limited-slip

differential, which was augmented by Dynamic Stability Control that

could be switched off altogether by the driver.

The M5 also got

stronger suspension components front and rear, stiffer springs and

dampers, and larger brakes than the standard 540i. Those upgrades made

the M5 a formidable weapon around the Nürburgring Nordschleife, which

it could lap in just eight minutes, 20 seconds with a skilled driver

at the wheel. That driver was usually Gerhard Richter, who took over

the M division in 1997, when Kalbfell was promoted to lead BMW’s

global marketing department. Richter had been Head of BMW M Technical

Development since 1994, and he performed final testing of all of BMW

M’s automobiles. “There aren’t a lot of race drivers who have as many

laps around the Nordschleife as Gerhard Richter,” Hildebrandt said.

“He had some strict ideas about what an M car should feel like,

including making the suspension as stiff as possible to make the car’s

steering and reactions as precise as possible.”

To ensure

stability at speed, the E39’s exterior styling (by Joji Nagashima) was

given subtle but effective aerodynamic upgrades from Marcus Syring,

who also designed the car’s unique 18-inch M Double Spoke wheels.

Syring gave the M5 a front spoiler inspired by that on a proposed Z3

coupe race car, which provided downforce as well as increased airflow

to the S62 engine; this was matched to a small Gurney flap on the

trunk lid.

While the car was under development, Brekus was

working to persuade BMW NA President Vic Doolan that a new M5 could

succeed in the US. “Doolan was adamant that he didn’t want to repeat

the disaster of the E34 M5, but agreeing with Germany on a reasonable

price point [$69,500] for the E39 M5 helped convince him, as did the

fact that the E39 was a great car even as a non-M,” Brekus said. “I

think Carl-Peter Forster deserves a lot of credit for making the E39

platform so good from the ground up.” BMW NA signed on, and the E39 M5

debuted at the Geneva Auto Salon in March 1998. Global production

began that October, with production of cars for the US slated to start

in September 1999. In the meantime, BMW NA’s product planners worked

to define the car’s specifications for this market. “BMW AG offered

the US market a wide array of options, which we tried to cull into a

more simplified offering for BMW dealers and showroom staff,” said

Scott Doniger, who replaced Erik Wensberg as BMW NA’s M Brand Manager

shortly after the Geneva show. (After European launch, Hildebrandt

left BMW M, too, with Albert Biermann completing the M5’s development

for the US.)

All M5s got heated sport seats, an M steering wheel and M

instruments, plus features like Xenon headlights and satellite

navigation that were optional on other E39s. The M5’s interior was

beautifully appointed, with extensive leather in a variety of color

combinations, including three two-tone options. Combining those

features with superb performance—the M5 could accelerate from zero to

60 mph in just 4.8 seconds—yielded what Doniger called “a superbly

balanced and responsive luxury sports car, something new that had

never existed before.”

“It’s one thing to throw a V8 into a

four-door sedan and make it go fast in a straight line,” Doniger said.

“A heavy front end typically unbalances a sedan, but the M5 didn’t

feel like a heavy sedan. The package just worked holistically, with

phenomenal handling balance under acceleration or braking, and

especially in cornering.”

About two months after the E39 M5 launched in the US, Doniger

left BMW NA for other opportunities. He was replaced as M Brand

Manager by Tom Salkowsky, who witnessed the M5’s incredible success in

the US market. “One of our biggest challenges was allocation: We

couldn’t get enough production to meet consumer demand,” Salkowsky

said. “One of our best talking points was the six-speed manual

gearbox, which was a major differentiator to the Mercedes E55 and

Jaguar XJR. The pairing of a manual transmission and near 400

horsepower [394 in US spec] was pure magic, and customers loved that

thisM5 was built for enthusiasts, for drivers who were skilled enough

to master a manual transmission and nearly 400 horsepower.”

To

ensure all M5 buyers had those skills, and to demonstrate the car’s

true capabilities, the $69,700 list price of every new M5 included a

day at BMW NA’s newly-opened Performance Center in Greer, South

Carolina. Driving BMW-owned M5s on the Performance Center’s track,

customers could discover their new cars’ capabilities in relative

safety.

The E39 M5 arrived in the US shortly after the E36 M3

went out of production following a five-year run of extraordinary

success in this market. “The sales momentum was building, the energy

and excitement around these dynamic M cars was growing, and it helped

the US gain a stronger voice in Munich,” Salkowsky said.

It

hadn’t been deliberately designed for the US—indeed, its “American” V8

had come about organically, as the answer to a technical problem

rather than a marketing concern—but the E39 M5 seemed tailor-made for

the US market. By the time production ceased in June 2003, US

enthusiasts had snapped up 9,198 examples—nearly half of the 20,482

E39 M5s built for worldwide consumption.

Even more surprisingly,

the M5’s production-based S62 V8 engine made its way to the racetrack.

With the six-cylinder S50 no longer competitive, Tom Milner’s

engineers adapted the S62 V8 to the Jet Racing E46 M3 for the Grand-Am

series. At the 2001 Daytona 24 Hour race, the car ran a competitive

fifth in the GT class until an air filter clogged with water. Later,

Steve Dinan would build S62-based racing engines for Daytona

Prototypes; Chip Ganassi’s BMW-powered Rileys won the Daytona 24 in

2011 and 2013, along with the Grand-Am engine manufacturer

championships in both years.

It was an impressive record for a production-based M engine, and

it offered a powerful endorsement for the V8 engine concept that would

drive subsequent M5s as well as the E9X M3. Those cars might not have

been built if the V8-powered E39 M5 had failed to catch on among US

enthusiasts. “Without the V8, we wouldn’t have had a chance to get the

US on board,” said Hildebrandt, “and without US volumes the project

wouldn’t have been profitable at all.”

Along with the E36 M3,

the E39 M5 turned the US into the world’s largest market for M cars

worldwide, helping to ensure the M brand’s future within BMW

worldwide. Moreover, the V8 engine helped catapult the E39 M5 into a

higher echelon of performance, setting the stage for all the M5s that

have followed. “The E39 positioned the M5 as a thoroughbred

super-sedan, and it created a great foundation on which future M5s—the

E60, F10, G30, and now G60—could build upon and elevate,” Salkowsky

said. “And overall, it helped BMW M position itself as a brand that

blended ultimate performance, innovation, and technology with

refinement.”

—end—